My novel Unbound touches upon many topics that we are facing today, such as life under oppressive political systems, a woman’s right to make choices for herself, and so forth. It is set against the historical backdrop of Shanghai, China in both the 1930s and 1970s. Many readers may not be familiar with this history and the culture of these times. So, I provide some background for the reader to refer to.

Shanghai Before the British

The great city of Shanghai has a relatively short history by Chinese standards. For many hundreds of years, Shanghai was just another Chinese fishing village, positioned at the end of the vast delta formed by the Yangtze River.

Through the centuries, the Yangtze delta created an agricultural heartland. The delta provided rich soil for growing rice and cotton, the latter in turn leading to an early cotton industry by the mid-1800s.

The First Opium War and Humiliating Treaty of Nanking

In the 1800s until 1911, Shanghai and China were ruled by the Qing Dynasty. The Western powers saw China as a vast market to sell their goods. The British in particular saw China as a huge market for opium harvested in their colonies in South Asia.

When the Qing government attempted to stop these opium imports, Britain responded by waging war on China in what became known as the first of the two Opium Wars.

The war was a disaster for the Qing, who were forced to sign a humiliating Treaty of Nanking in 1842. The Treaty opened up Shanghai as one of four ports for Western countries to trade. In addition to surrendering the control of trade in Shanghai, the Treaty of Nanking ceded Hong Kong, which became a British colony.

Shanghai’s Rapid Growth as a Foreign Concession

Shanghai’s Rapid Growth as a Foreign Concession

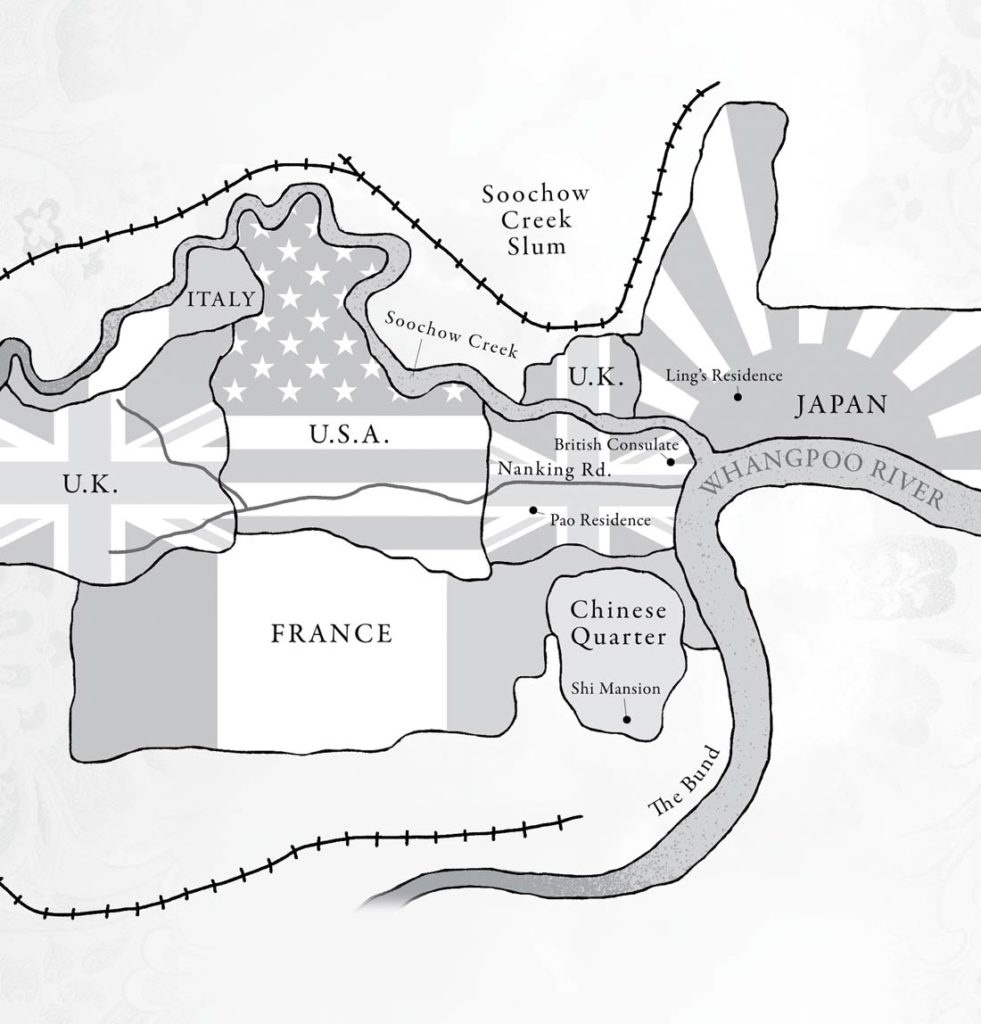

Two years later, the British carved out a section of Shanghai, and set up their own government. The British were soon joined by the French and American powers, which negotiated their own concessions.

Shanghai was at that time still a small port town. That was to change quickly.

Shanghai’s rapid growth benefited from two things. The first was its location at the mouth of the longest river in China. The second was a massive rebellion that broke out shortly after the Qing’s defeat at the hands of the British. For nearly 15 years from 1851-1865, a religiously-inspired Taiping rebellion caused devastation throughout much of China. Shanghai remained a haven, and the city and its river became the most important means of trade with inland China.

Many western businessmen seeking fortune settled in Shanghai in the late 1800s. The British and Americans eventually merged their concessions into an International Settlement governed largely by the British. And, after Japan defeated China in its own war in 1895, the Japanese won their own concession and developed it into a rival concession in Shanghai.

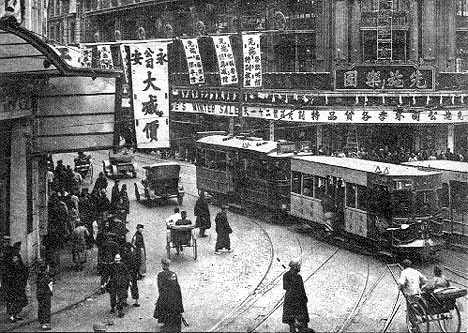

By the dawn of the 20th century, Shanghai would become the largest port in China. And by the 1930s, Shanghai had become one of the largest cities in the world with more than three million inhabitants, including as many as 50,000 westerners.

The foreigners lived in the British, French, American, German and Japanese concessions, occupying nearly half of Shanghai. These foreigners were not subject to Chinese law. They were a class apart form the Chinese who lived among them in Shanghai.

The Chinese living within the concessions typically held a modern and westernized outlook. They were not tied to the land, and instead tended to be industrialists, intellectuals, or professionals working for the foreigners. This cultural divide is reflected in Unbound, where you see the tension between the Pao’s who live in the British concession and the Shi’s who live in the old Chinese district.

The Bund

The foreigners developed the Bund into the city’s most important place of government and trade. Located in the British concession, the Bund is a long strip of waterfront and road along the Huangpu River, which connects with the Yangtze River. On one side is a grand park overlooking the river.

The park was restricted to foreigners and the signs that prohibited Chinese and dogs from enjoying the park humiliated passing-by Chinese. Again, Unbound touches upon this sensitive subject. On the other side of the road were many imposing and magnificent buildings that housed trading firms, banks and insurance companies, and the British consulate.

The Bund in the 1930s projected the Western countries’ absolute power and wealth in Shanghai.

Fashion in the 1930s

Fashion in the 1930s

Shanghai was by the 1930s the Paris of the East. It was a cosmopolitan city that reflected the marriage of east and west. This was especially noticeable in Shanghai fashion, which mixed western and traditional Chinese styles.

Well-to-do men with a traditional Chinese mindset continued to cling to their traditional changshan, a long tunic or gown. Some would also take to wearing a suit jacket over their changshan. The tunic could be made by any kind of fabric, from silk, satin to plain cotton. It was the quality of the fabric and workmanship that indicated the wearer’s social and economic status.

Young men were increasingly a westernized generation. They would wear the latest fashions, mimicking the English who ruled the city. They favored suits and ties and Oxford shoes—the two-toned spectator version, playfully called champagne shoes by Chinese locals.

Laborers would wear a two-piece top and bottom that was loose and easy to wear while working. Their shoes would be a simple pair of homemade cotton slippers.

For women, the traditional qipao never went out of style and remained a common dress for young and old alike. It was the cut of the qipao that made all the difference. The 1930s qipao had become a skintight dress, with a slit on the side that over the years grew progressively longer, revealing more leg. Young and sophisticated women favored these tight qipao and old and conservative women favored an old fashioned, shapeless and loose one. As with a man’s tunic, the fabric and workmanship indicated a woman’s class. Women who worked as servants or took on other labor would wear a loose two-piece outfit, like the men.

Like men, women increasingly adopted the shoes worn by western women, a low-heeled Mary Jane. Others would continue to wear the traditional slipper. These would be embroidered satin slippers for the well-off and simple cotton slippers for the working class.

Any woman who had her feet bound was by definition traditional. I separately discuss the horror of the foot-binding fetish below, and how the practice physically bound women to the home.